Your basket is currently empty!

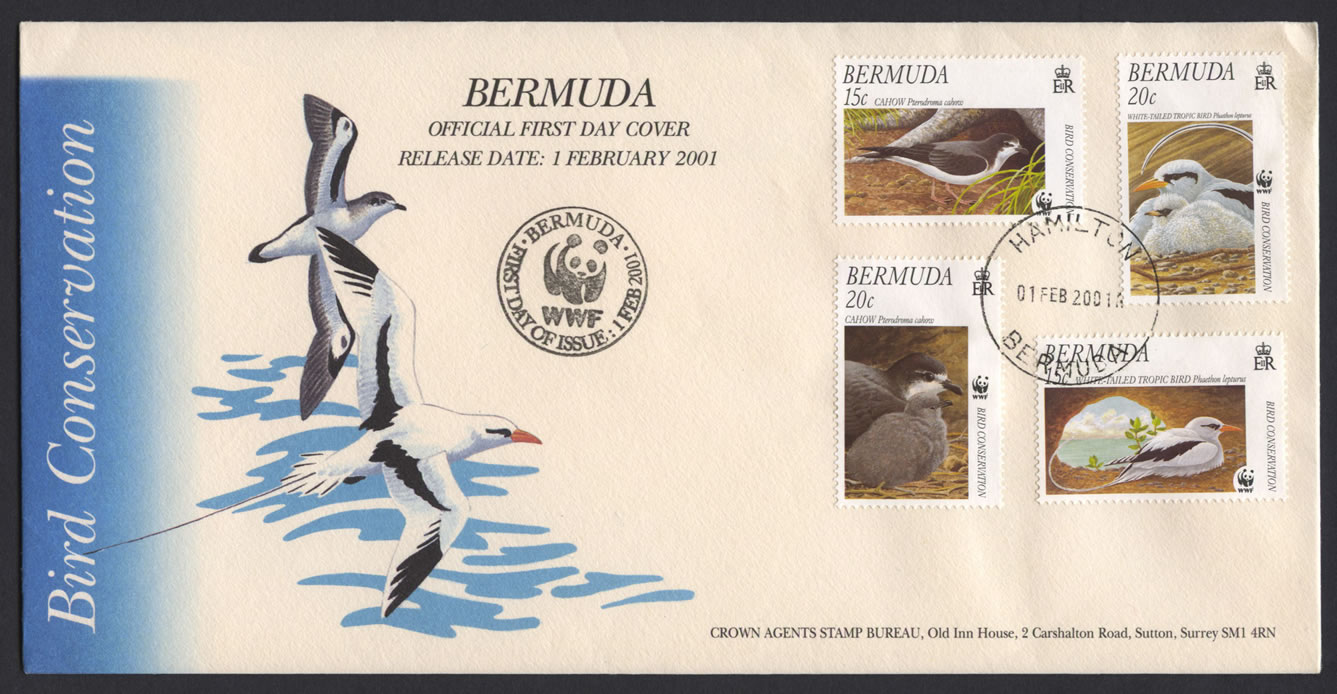

2001 WWF Bird Conservation

World Wide Fund For Nature issue

Date: 1st February 2001

Type: Official First Day Cover

CDS: BERMUDA

Cachet: Bird Conservation / BERMUDA OFFICIAL FIRST DAY COVER / RELEASE DATE: 1 FEBRUARY 2001

Hand stamp: BERMUDA FIRST DAY OF ISSUE : 1 FEB 2001 WWF with Panda

Address: Crown Agents Stamp Bureau, Old Inn House, 2 Carshalton Road, Sutton, Surrey SM1 4RN

Stamps: BERMUDA BIRD CONSERVATION 15c and 20c CAHOW Pterodroma cahow; 15c and 20c WHITE-TAILED TROPICBIRD Phaethon lepturus

Liner

BERMUDA

WWF/BIRD CONSERVATION

Bermuda Petrel or Cahow

Pterodroma cahow

In 1951 Dr Robert C. Murphy, a world authority on seabirds, and Louis S. Mowbray, Curator of the Bermuda Aquarium and Museum made headline news around the world when they announced the rediscovery of the Cahow – a Seahird which was thought t0 have become extinct about the same time as the Dodo.

The Cahow had survived against almost impossible odds. Originally the most abundant of Bermuda’s seabirds it proved exceptionally vulnerable to introduced mammal predators on account of its burrow nesting habit. Like most female oceanic islets, Bermuda had no indigenous humans or other mammals so the seabirds had never evolved any defences against them. Within a decade of senlement in 1612 their population was decimated by imroduced pigs, dogs, cats and rats and by the settlers themselves as a food source.

Nevertheless, incredibly, a few managed to survive undetected for three and a half centuries on a few tiny off·shore islets. Their toe·hold was so marginal, however, that lack of soil for burrowing forced them to occupy the cliff-hole nesting niche of the larger tropicbird or “Longtail”. The resulting nest·site competition caused such a high mortality of the nestlings that the population had to decline.

In 1951 there were only 18 pairs left.

Inspired by the rediscovery, the Bermuda Government declared all of the Cahow nesting islets as sanctuaries and launched a conservation programme with international assistance. The prospects seemed hopeless at first, but gradually the problems were overcome.

During the 1950’s an artificial entrance to the nests, called a ‘baffler’, was developed to exclude the larger Longtail. This simple, but ingenious device effectively trebled the Cahows breeding success after 1960. Subsequently artificial nesting burrows were provided to overcome the problem of lack of soil for burrowing and to accommodate the amicipated increase. Now, forty five years later, the population has trebled to more than 50 pairs, of which two thirds are nesting in artificial or enhanced natural burrows.

Progress has heen slow on account of the inherently low reproductive capability of the Cahow – they lay only one egg a year and half usually fail. The programme has also suffered some c1iff.hanging setbacks. During the 1960’s a DDT pollution reduced breeding success in the Cahow in the same way that peregrines, eagles and ospreys were affected. In 1987 a vagrant snowy owl killed at least 5 birds, and in 1995 a passing hurricane overwashed the nesting islets destroying nearly half of the nest·sites. Programme managers had only one month to repair the damage before the birds returned for another nesting season!

Partly in amicipation of this hazard steps were taken 35 years ago to set aside a larger island, known as Nonsuch, which had adequate soil cover for burrowing. This has since evolved into the Living Museum Nature Reserve project which has acquired an international reputation as a success in Holistic Restoration.

White-Tailed Tropicbird or Longtail

Phaethon lepturus

Bermuda is one of the few places in the world where the widespread tropical island nesting Longtail maintains a large population in close proximity to man. This is due in part to its habit of nesting in cliff-holes where it is secure from predators, and the fact that Bermuda has extensive coastal cliffs of porous limestone rock which erodes unevenly to produce innumerable holes and crevices. However, it is also due to the high degree of protection it receives from Bermudians who treasure it as the traditional harbinger of Spring.

Longtails return to land from their wintering ground in the Sargasso sea in March and nest over the summer months. Groups of these satiny white and black patterned birds with their extraordinarily elongated central tail feathers make a spectacular sight as they perform their tail touching aerial courtship against a background of cerulean waters and blue skies.

Longtails weren’t always treated so kindly on Bermuda, and some problems of an indirect nature continue to threaten them even today. During the nineteenth century, before legal protection, they were harvested for their long tails for use in the millinery trade. In recent decades the greatest threat has come from coastline development. This not only destroys some nest-sites outright but increases access by pet dogs and cats. Unless carefully restrained, terrier breeds can habituate to killing and can reach a surprising number of nests, especially those located under talus at the base of cliffs.

Like most other oceanic island birds, Longtails are vulnerable because they have no inherent fear of introduced mammal predators. But unlike the Cahow, their tiny paddle~like feet are too small for walking so they land and take off directly between the nest-hole and the ocean without making any other contact with land.

This unique combination of behaviour can be used to advantage by conservationists because it is only necessary to create nest holes in vertical cliffs, terrace walls or other places inaccessible to guarantee security from predators. Proximity to human habitation is not a problem. If enough of these safe nest holes could be provided the Longtail population could service even in a totally urbanized environment. It is towards this end that conservationists are presently developing an artificial nesting cavity with mass production capability, using a new lightweight roofing material developed on Bermuda.

Kind acknowledgements are given to Dr David B. Wingate, for providing liner information and reference material.

World Wide Fund For Nature

The sale of stamps has become an important source of income for funding WWF’s conservation activities. With one billion stamps printed and 280 issues from 200 Countries, by the end of 2000, WWF has so far received 18 million Swiss Francs in royalties.

The first WWF issue was the Sierra Leone Chimpanzee issue released in 1983. Since that time the WWF Conservation Stamp Collection has grown into the largest thematic collection in the world, with some 900 different stamps released.

The money from their sale has helped fund activities from the conservation of endangered species, to helping rain forest and coastal dwelling communities improve their standards of living through the sustainable use of their natural resources.

Each year up to 18 different countries issue stamps featuring their own threatened animals.

TECHNICAL INFORMATION

Designer: Norman Arlott

Printer: Questa

Process: Lithography

Stamp Size: 28.45mm x 42.58mm

Pane: 50 (2 x 25)

Perforation: 14 per 2cms

Paper: CA Spiral Watermarked

Values: 2@20c; 2@15c

Release Date: 1 February 2001

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.