Your basket is currently empty!

British Imperial Censorship

Bermuda the World War II hub

At the outbreak of World War II censorship departments were set up across the British Empire with the main headquarters in Liverpool chosen since it was a important shipping port and the perception that it was less likely to be bombed than London.

At the outbreak of World War II censorship departments were set up across the British Empire with the main headquarters in Liverpool chosen since it was a important shipping port and the perception that it was less likely to be bombed than London.

Bermuda became a satellite Ultra establishment and was turned in to Britain’s No. 1 listening post during the Second World War for censorship and contraband control under the British Imperial Censorship. Ultra was the designation adopted by British military intelligence in June 1941 for wartime signals intelligence obtained by breaking high-level encrypted enemy radio and teleprinter communications at the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) at Bletchley Park.

Due to Bermuda’s strategic position, the bulk of letter mail and parcel post between the Americas and the rest of the world passed through it during this time. So did the large part of other international mail in the world except that going to England. A letter originating from Ceylon and bound for Vichy would be sent via an elaborate route passing through Bermuda.

Every day ships would drop anchor in Bermuda to pass the Censorship, and transatlantic Clippers would pause in Bermuda for examination of their mail.

All of this activity was done under a veil of secrecy and even a request from local Bermuda journalists for the exact number of staff working for the Imperial Censorship in Bermuda, was rejected. This figure was later to be estimated at 1 censor for every 30 islanders – about 880, although figures at its peak were said to be 1,200. All the work was done behind closed doors and the Censorship got its first publicity when mail was removed from an American Clipper bound for Lisbon – this action later being dubbed as the “The Great Plane Robbery.” Captain Lorber protested that he had been threatened by British marines with fixed bayonets, which was of course was flatly denied by James Pantan, the censor in charge at the time.

The Imperial Censorship commandeered the Princess Hotel on the Hamilton waterfront for their offices and staff resided in the Bermudiana and the Inveruric hotels with their two swimming pools and half a dozen or so tennis courts. The censors had their own table tennis team, dramatic club and they even had an Imperial Censorship Choir.

Censor profiles

Censors preferably had to be British citizens being drawn from all over the Commonwealth and Empire. Chosen for their knowledge and language skills to examine the letters from all over the world. Some staff profiles include a Swiss florist, the former manager of the Anglo-Czechoslovakian Bank of London and a Cambridge University professor with a command of 30 languages including rare Indian dialects. Others who have worked for the Imperial Censorship in Bermuda are Val Gielgud, a BBC producer, Eric Maschwitz, author of Balalaika, a doctor who was at Dunkirk, a biographer of obscure French philosophers and a Scottish girl with a command of 10 languages. Age was no issue with several eminent language scholars over the age of 80.

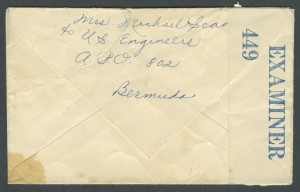

The vast majority of the censors were women and known as Examiners, or informally as “Censorettes”, and drawn from the British Post Office Department, schools and libraries with the majority being older spinsters.

Letters were tested for secret inks and the Bermuda Censorship became the top scientific testing laboratory headed up by Charles Dent, a young doctor.

No language a barrier

The Imperial Censorship claims to have never opened a letter in a language it could not read. A launch was sent out every day to make the rounds of the newly arrived ships and would bring the mail alongside the Princess Hotel where it was sorted in to coloured bags: red for the US,; blue for Argentina; green for Mexico and so forth. Each bag was weighed, counted and checked to account for every letter. Some idea of volume would be the fact that a single eastbound aeroplane will leave 45 to 90 bags, one westbound from 75 to 150 with some bags containing as many as 1,000 letters.

The Imperial Censorship claims to have never opened a letter in a language it could not read. A launch was sent out every day to make the rounds of the newly arrived ships and would bring the mail alongside the Princess Hotel where it was sorted in to coloured bags: red for the US,; blue for Argentina; green for Mexico and so forth. Each bag was weighed, counted and checked to account for every letter. Some idea of volume would be the fact that a single eastbound aeroplane will leave 45 to 90 bags, one westbound from 75 to 150 with some bags containing as many as 1,000 letters.

Charles R Watkins-Mence, Controller of the Censorship stated that his staff was so large that “We keep nothing beyond one Clipper.” After checking the mail goes upstairs to an examination room where hyndreds of women examiners under the discipline of roving overseers, break it down in to groups by subject matter; private and business, shipping, commodoties, metals, etc.

Languages are divided in to common and uncommon. Common includes English, French, Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, Dutch, German, Norwegian, Swedish and Danish, and many censors can handle three or four at once. Smaller groups of experts study the uncommon languages: Greek, Latin, Ukrainian, Hungarian, Polish, Russian, Ruthenian, Lithuanian, Finnish, Yiddish, Hebrew, Croatian, Serbian, Czech, Catalan, Romanian and Japanese.

The censors worked long hours often seen cycling to work as early as 6.15am or finishing work at midnight the day before a Clipper leaves. Nothing stopped afternoon tea however, served on mass from heavy American dog-wagon-type mugs off tressle table in the hotel lobby.

The Censorship had its own MI (Military Intelligence) for its job was not only to keep information from reaching the enemy but to intercept useful items for the British armed forces. For example, the censors opened a letter from Italy in which the writer complained that armoured trains were passing through the coastal town of Porto di Reggio every night disturbing his sleep. This information was passed on to the British Mediterranean Fleet who conducted bombardments at night.

Censorable material

When censorable material is found, officials snip out the offending passages with scissors with occassional incautious letters cut to ribbons.. Many letters which pass through apparently uncensored have actually been copied and sent to London. Some are photographed on 35mm film and blown up to bring out every detail. Others are destroyed and stored in old sacks, piled up like sand bags in plain view under the sun porch of the Princess.

When censorable material is found, officials snip out the offending passages with scissors with occassional incautious letters cut to ribbons.. Many letters which pass through apparently uncensored have actually been copied and sent to London. Some are photographed on 35mm film and blown up to bring out every detail. Others are destroyed and stored in old sacks, piled up like sand bags in plain view under the sun porch of the Princess.

A great deal of of mail, especially to and from Bermuda itself, is not even opened if the censors know the sender or recipient. Objects of invariable search by the censors are letters from Jamaica and Ireland, which they suspect of disloyalty, and US letters bound for Germany which are marked “Via Siberia”. In commenting on American aid to Britain, one censor remarked that he personally had seen a number of these.

The greatest part of the censor’s work is to keep the lid tightly clamped on Britain’s strict currency control, designed to keep the value of the pound from falling below the pegged rate of 84.04. The censors watch for fake business deals, often from Buenos Aires, by which Britons or neutrals try to salt away British funds to the safety of the United States.

Contraband auctions

The Censorship works closely with revenue officials to seize all contraband sent by mail or parcel post. Together they have intercepted various Nazi attempts to raise funds in America, including shipments of ambergris, and art raided from the Louvre. Since last December Censorship-seized contraband has been sold at public auction three times a week under the No.1 shed on Hamilton waterfront. Most of the seizures, were testament to Europe’s shortages, have been packages of canned goods, meats, tea, coffee, cocoa, sugar, edible oils, powdered milk, tapioca, Crisco (shortening), chocolate, tobacco – and always soap. Most of it was derived from Occupied France, some from enemy territory. The boxes, many bearing familiar labels from Macy’s, Bloomingdale’s and the A & P, average a cubic foot in size. An auctioneer in a loud chequered tweed jacket knocks them down to group of local Bermudians, at prices high for the US but low for Bermuda which must live off imported food. The auctioneer opens ands displays all the objects before sale, to the disdain of some who prefer a surprise.

One of the best auction stories is still shrouded in mystery. It concerns a shipment of rare cyclamen seed, valued at between $5,000 to $15,000 from Holland to New York. Suspecting that this was a Nazi attempt to raise foreign exchange, the censors seized the shipment and, shortly afterward, the worried Dutch consignees in New York sent an agent to try to buy it back at auction. Unable to find out in advance when it would be sold, the agent for five weeks patiently showed up at 11am for the start of the auction. Thereupon the censors discovered what was afoot, one day started their auction at 10.30am. When the Dutchman arrived half an hour later, the seeds had been sold for £5 to a Bermudian who promptly travelled to New York, sold them from $4,000 and turned the money over to the Bermuda War Fund. This intricate, conscienciously legal and thoroughly British coup was hailed as a great triumph over Axis coniving, even though it later came out that the Dutch agent had been ready to considerably more than $4,000 right at the auction.

Spy rings

Censorship first appeared on a major scale during World War I and plenty of lessons were learned by the British which were put to good use during World War II. Even before the United States had joined the war, the British Imperial Censorship had caught two major German spies in the United States and its protectorate Cuba.

In December 1940, one of the 1,200 examiners at Bermuda stopped a letter addressed from New York to “Lothar Frederick, I, Helgolaender Ufer, Berlin”. He became suspicious as it listed Allied shipping and used unusual wording, such as “cannons” for “guns” when describing ships’ armament, suggesting the writer may be German and a possible Nazi agent. The letter was signed “Joe K.” A watch was set up for letters with his handwriting soon produced quite a few more, mostly to Spain and Portugal. The language seemed slightly forced, and a team began studying the letters to see whether this indicated an open code and, if so, what it meant.

One member of the team was a persistent young woman called Nadya Gardner, who bedame convinced that the letters contained invisible writing. The usual strip tests with chemicals that bring out the ordinary secret inks gave negative results, but Miss Gardner persisted. Finally the chemists, under Dr Enrique Dent, applied the iodine-vapour test invented back in World War I – and to their surprise secret writing did appear on the back of the typed sheets.

A letter of six days later, addressed to a Miss lsabel Machado Santo in Lisbon, reported in invisible ink that “British have about 70,000 men on Iceland”# The S.S. Ville de Liege was sunk about April 14-many thanks # Types of airplanes flown to England (continued from lett r 69)-3. Boeing B-17c (model 299T) twenty were released by the U.S. Army to Britain on Nov 20 …”

These little billet-doux were ‘written in a solution of pyramidon, a powder often used as a headache cure and readily obtainable at most pharmacies. But there was till no clue as to the sender. The letter bore no r turn address, and it was rather unlikely that “Joe K” was the spy’s real first name and last initial. Finally British censorship picked out another Joe K letter that reported that ‘Phil’ had been fatally injured in new York traffic accident on March 18 and had died at St. Vincent’s Hospital. FBI agent found that the man in the accident was known as Julio Lopez Lido and that witnesses had seen that a man with Lido had grabbed his briefcase after the accident and hurried away. Eventually, the agent learned that Lido’s true name was Ulrich von der Osten and that the writer of the Joe K letter was Kurt Frederick Ludwig. Ludwig, born in Ohio but raised in Germany, had come to the United States in March of 1940 to organise a Spy ring. which he had done with moderate success, When captured he had several bottle of pyramidon in his posession. The odd one of the open text of his letter was accounted for by its double meanings. “Your order 5 is rather large – and I with my limited facilities and fund shall never be able to fill such an immense order completely, ‘ he wrote to one of his addressees all of them, incidentally, cover addresses for Himmler. This message really meant that he would have difficulty fulfilling the instruction sent to him in communication No. 5 because of too few agents and too little money. Ludwig was convicted in the U.S. District Court at Brooklyn.

The second spy trapped by the alert Bermuda station went to his death. On a November day in 1941, an alert censor detected a rather Germanic cast to the handwriting in a Spanish-Ianguage letter from Havana to Lisbon and sent it over for a routine test for scret ink. His intuition was confirmed when a long missive appeared, listing ships being loaded in Havana harbour and discussing an airfield being constructed. The examiner were alerted to watch for similar handwriting. The next letter turned up a few day later. Censorship continued picking out these letter, which recited detaiIs of merchant shipping in Cuban waters and the enlargement of the US Navy’s base at Guantanamo Bay, until the writer’s real Havana address showed up in secret ink.

To be continued!

At the end of the war

During World War II the Censorship has did not suffer the same embarrasment it received after World War I, when a top man in the Liverpool Censorship turned out to be a German agent. It took no chances during the Second World War with a British secret agent implanted amongst their number and all their own mail subject to censorship too.

The majority of censors in Bermuda returned to the United Kingdom in May 1944.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.